75

Reflections on Class, Struggle, and Solidarity

There is an interesting discussion currently going on at my friend Victor Serge's blog, Monuments are for Pigeons (formerly titled And your little dog, too). Victor and his cadre of Marxist blogger friends had the great idea of holding a virtual reading group. The plan is to choose a book, and have each member of the group host a discussion on his or her blog about one of the chapters. The first book they're reading is Perry Anderson's 1976 book Considerations on Western Marxism.

Not having read Considerations on Western Marxism (and not having much time to delve into it right now), I feel hesitant to enter the conversation on Victor's site; is there anything more annoying than that member of the reading group who shows up -- if virtually -- without reading the book?! But Victor's commentary on Chapter 1 of Anderson's book raised some questions for me, which I feel compelled to discuss. (Since this post directly engages the discussion on Victor's blog, I suggest that you read that discussion-- including the comments -- before proceeding).

In particular, I want to contest the claim that Victor made in a comment following his first post (to which other posters implicitly or explicitly assented) that "there's fuck-all going in the struggle on right now, at least in North America" and that, consequently, "[o]ur tenuous links with class struggle threaten to devolve into a moral commitment to other people's class struggle".

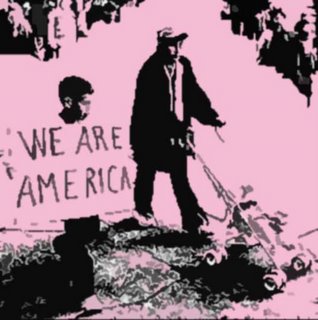

In my estimation, the first part of the claim, i.e., that there is no class struggle currently being undertaken in North America at the present time, is just empirically incorrect. We just witnessed, earlier this spring, the largest demonstration in recent memory in the U.S.

we are america.

may day 2006.

On May Day, 700,000 immigrant and non-status workers marched in Chicago; over 1 million in L.A. (and 72,00 students, approximately 1/4, walked out of classes); 75,000 in Denver; 100,000 in New York City. In a recent article published on Znet and republished in New Socialist, Brian Kwoba argues that this uprising of immigrant labour represents the "birth of a new left". (I would add to Kwoba's claim that immigrant and migrant workers have always been, in Canada and in the U.S., at the forefront of class struggle and revolutionary politics. So I am not sure to what extent we can call this something "new" -- it is perhaps better thought of as a "resurgence" or "rejuvenation" of a long tradition of resistance.) In Montréal, where I am based, there's an active, militant, community-based movement for the regularization of non-status migrant and refugee people. Given that the politics and vicissitudes of (im)migration are inextricable from the needs of capital, these have to be understood -- indeed, they have to be seriously analyzed -- as instances of class struggle. The anti-colonial resistance of First Nations people for self-determination would also be productively read in these terms.

If this sounds like a strange proposal, perhaps it is because of the way in which -- despite their claims to the opposite -- many Marxists continue to conceptualize "class" and "class struggle". It seems to me (and here I go on to make a polemical generalization without providing much by way of evidence) that even as antiracist and feminist critiques of Marxism are nominally embraced by the political centre of Marxist thought, the categories of analysis remain more or less unchanged. What would a Marxist analysis that put immigrant racialized women at the centre look like?

The claim that there is no class struggle going on in North America (which I assume excludes Mexico in Victor's original formulation) -- or in the Global North more generally -- renders invisible the struggles of racialized, minoritized, and gendered communities, for whom class struggle takes place not only at the macropolitical level (as the May Day demonstrations evince) but also at the micropolitical level: in the terrain of the everyday; in the so-called private sphere; in regions of social life which an analysis which understands "class struggle" in classical terms might not be able to comprehend.

who will pick your tomatoes?

a slogan of the "day without immigrants"

On a related point, I worry about this nostalgia for the glory days of classical Marxism, which supposedly manifested a praxiology and a worldly orientation which Western Marxists or contemporary Marxists ostensibly lack. It may be true that one is a better Marxist if one is enmeshed in revolutionary struggle; but how do we understand "revolution" or "revolutionary politics"? What does a revolution look like? Who is the normative subject of this revolutionary politics (i.e., who is the representative figure, the ideal-typical person on whose behalf this politics agitates?)? Do revolutions take place only in street battles with bayonets, or might they also be said to take place in bedrooms and in kitchens? Is not this nostalgia for a Marxist past a way to avoid confronting the real battles in the political present, and the shape that these battles take? Such a confrontation might require that we develop new categories of analysis, new ways of understanding the political problem, and that we privilege different -- i.e., heretofore marginalized -- subjects of collective struggle.

Finally, I'd like to say something about the second part of Victor's claim, i.e., that "[o]ur tenuous links with class struggle threaten to devolve into a moral commitment to other people's class struggle". I have two questions to pose in response here.

First, I don't understand this idea of "other people's class struggle" -- is there not one class struggle, which transcends the borders of nation-states, of categories of "race" and gender, which exceeds the geopolitical divisions between Global North and Global South? As a member of the (international or transnational) working class, when I engage in this struggle, am I not struggling for the total transformation of society? Isn't this the supposed advantage of revolutionary socialism over so-called "identity politics"? That is, that it provides a way to understand my local experience of exploitation and oppression in terms of globalized structural relations?

Second, it seems to me that one of the most pressing and intractable problems of political resistance -- and this is by no means principally a theoretical problem -- is presented by the question of how to organize across lines of difference produced by dominance (e.g., across lines of "race," gender, and class); in other words, how to form political coalition with global Others; how to struggle -- in some cases -- against one's immediate interest; how to transcend one's descriptive social location (e.g., bourgeois white citizen of the global North) in solidarity with a "universal" politics of social transformation; how to conceptualize and relate to one's political allies, and so on. Framing political solidarity or participation in global struggle as "moral commitment to other people's class struggle" seems to suggest that such questions should take a back-seat, so to speak, to a class struggle that is properly one's own. But surely this is a false dilemma, if we want to maintain a simultaneous political emphasis on the local and on the global aspects of class struggle?

What is more, to return to the question of the relation between historical struggle and Marxist theory, it seems that Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky, all had this -- implicitly -- in mind. When I teach Marx to undergraduate students, one of the first questions they have is why and how would someone like Marx -- a university educated petit bourgeois philosopher -- become involved in, and devote his life to the revolutionary overcoming of a social formation which conferred on him relative social privilege? In other words, why and how would someone take on -- as a life project -- "other people's class struggle"?

Marx and Engels inspire these students to think about their relation and the nature of their commitment to a project of social transformation that does not follow immediately from their "identity." I should think that, asMarxists, we would be the first to do the same.

1 Comments:

Sorry it took so long for me to respond - but if you keep leaving comments, I will eventually!

I take back the 'fuck-all' bit, it was a stupid comment, born of my frustration watching wars unravelling far away and feeling powerless. I was incredibly inspired (and blogged about, a sure sign of inspiration!) the Latino immigrant rights movement and the Six Nations struggle.

I certainly don't want to downplay solidarity movements: they were the basis of the New Left, the movement against fascism & the Spanish Civil War, and many others. Solidarity, as you point out, is a key value for socialists, and one that prefigures the kind of society we're trying to create.

However, I think there's a spatial/experiential dimension that comes into play. I can go to a meeting or demonstration about Atenco, and I think it's vital that more people do so. But I'm not the one being brutalized or sexually assaulted. It's happening to other people. I think that changes one's experience of struggle, and can - not always - lead to a sense of moral superiority vs. all the 'normals' who don't know/don't care. I think this is at the root of some versions of anarchist politics, 'waking up' the sheep. It comes from a refusal to engage with the humdrum, everyday manifestations of class struggle which might be less spectacular, but - as I think you're saying - are equally important. E.g. the difference between solidarity with the Metro hotel workers trudging around the line for months, vs. solidarity with an anti-G8 protest.

Finally, a word on scale, because I think there's a qualitative difference between, say Canada in the 20s and now. I think Anderson's point is not to idolize Marx et al for their own sake, but to recognize that they were products of an immensely different period, when revolutionary struggles swept across much of the world. I think those struggles are defineable, because they challenged the instutitions of state & capitalist power. It's not an accident that they created the most radical, thorough-going strategic critiques for revolutionaries.

History gives us a sense of what it was like when people in staid neighbourhoods used to battle strikebreakers; when armed black men and women patrolled their communities against police injustices; when workers could set up alternate forms of governance. Not to sound jargony, but I think class struggle brings about collective self-empowerment, which - with some notable exceptions - is lacking on the ground today in many places. This is not to idolize the past - and certainly not to criticize what is happening now. But it is to suggest that the left's fortunes are tied to class struggle, and the marginalization of the left today has material precedents.

Comradely,

Victor

Post a Comment

<< Home